Sample chapter from the upcoming

MARCH OF THE TITANS: THE COMPLETE HISTORY OF THE WHITE RACE

Prometheus edition

Volume III: Europe and The World

European Expansion into The New World

Chapter 1: “White Supremacy”—The Civilizational Racial Gap

Chapter 1: “White Supremacy”—The Civilizational Racial Gap

The one overriding characteristic of all European explorations of the world has been the development of what has come to be pejoratively known as “white supremacy.”

While this phrase has been subjected to a large amount of abuse and deliberate misinterpretation, the reality is that the notion of Whites, and White civilization, being more advanced than those of the nonwhite world was the direct result of the massive technological, scientific, and cultural gap which existed between the races at the time of the Age of Exploration.

In other words, the development of “white supremacy” was not the product of a fictitious “mean streak” among white people, or something which originated in slavery, but directly grew out of the fact that Europeans possessed self-developed technology, science, and cultural advantages which placed them in an uncontested position of superiority over the world’s nonwhite races.

This process inevitably led to a feeling of superiority among European colonialists, which was at first unsaid but later formalized and taken for granted.

It was only in the Far East, and specifically China and Japan, that the white explorers found advanced civilizations, and it was in these regions only that the notion of “white supremacy” never took hold to the extent that it did elsewhere in the world.

RACIAL CIVILIZATIONAL GAP CREATES “WHITE SUPREMACY”

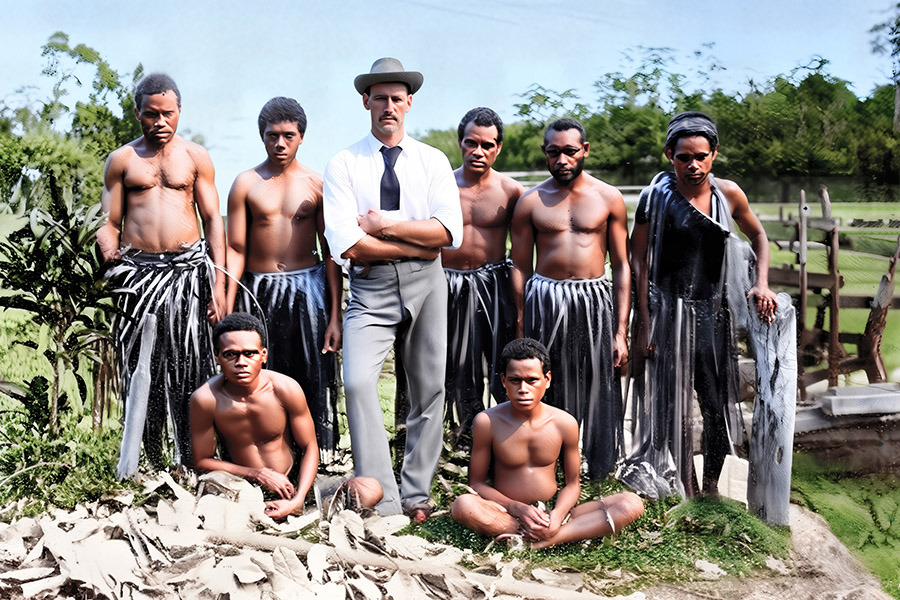

Above: The staggering disparities in technological, scientific, cultural, and civilizational levels between Whites and nonwhites during the Age of Exploration and Colonization led directly to the concept of “White Supremacy,” where Europeans could not help but consider themselves “superior” and in a position of paternalism toward other races. The error of their belief was that this situation would remain constant: as soon as the nonwhite races adopted White technology, medicine, education, and literacy, their populations, previously small before the arrival of Whites, exploded. As their numbers and education increased, they demanded political rights as well. This combination created the global racial political crisis that confronts the world in the present day. The extent of the racial gap can be seen in a 1900 photograph (restored and colorized) of a White trader on the island of Fiji. This image is valuable because it vividly demonstrates the cultural gaps that confronted early White explorers in 1900. (Photograph from The Right Hon. R. J. Seddon’s Visit to Tonga, Fiji, Savage Island, and the Cook Islands, p. 177, Wellington, NZ: John Mackay, Government Printer, 1900).

Technological Advantages

The list of technological advantages Europeans possessed over the nonwhite world was vast. Perhaps the most important from the point of view of exploration and colonization was that of weaponry.

The European weapons (muskets, arquebuses, and eventually rifles) provided an unbeatable advantage over all nonwhites in any conflict. European ships and forts were equipped with heavy cannons, while the use of iron weapons (swords and pikes), which had of course been known in Europe for thousands of years, was completely unknown to most nonwhites at the time.

The use of gunpowder and gunpowder weapons provided an invincible advantage in European conquests and defenses. Even the Chinese, whose impressive civilization had developed a crude form of explosive powder, were completely overwhelmed by the advanced European weaponry of the time and had nothing comparable to the European firearms or cannon.

The highly advanced European ships of the time were also far in advance of any vessel which nonwhite races possessed, with the closest rivals being found in China and Japan. Those two nations aside, the most that some nonwhite tribes had was a dugout canoe, and then, in many parts of Africa in particular, even that was unknown.

The vastly superior white technological advantage which underpinned the Age of Discovery is perhaps best illustrated with the appearance of the lone European sailor Charles Savage (?–1813, likely of Swedish origin), who single-handedly destroyed the native population’s power structure through the introduction of firearms on the island of Fiji.

In 1808, Savage sailed by canoe up a river in Fiji to the village of Kasavu, halting less than a pistol shot’s distance from the village fence. After being attacked, the lone White explorer defended himself by firing at the attacking villagers from a canoe in the middle of a stream adjoining the village. The casualties were so numerous that bodies were piled up as makeshift defenses, and the stream beside the village ran red with blood.

Hundreds of villagers, armed only with spears, were helpless against one white man and his gun.

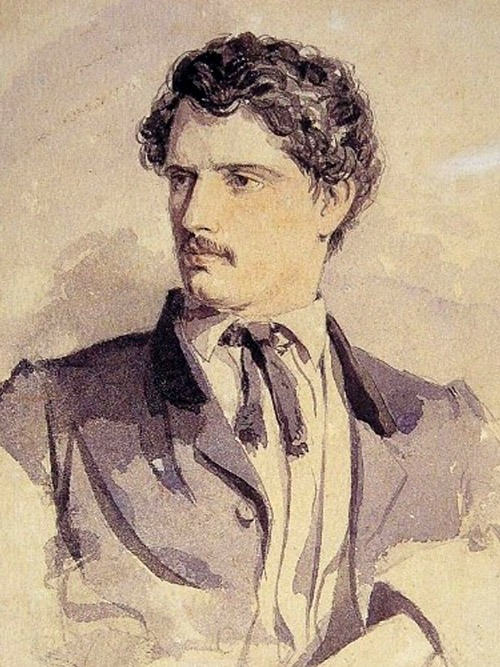

CHARLES SAVAGE AND THE CLASH OF RACIAL TECHNOLOGY

The technological gap that existed between the races was nowhere better demonstrated than in the 1808 clash between Charles Savage (real name Kalle Svensson) and the natives of the Fijian village of Kasavu. After being attacked by the tribesmen, Savage defended himself by firing at the attacking villagers from a canoe. The hundreds of natives, armed with pre-Iron Age clubs and spears, were defenseless against one European with a standard musket, and dozens were killed in the encounter. Savage went on to dominate the entire island and become one of its most important colonial era figures. Above, a portrait of Savage.

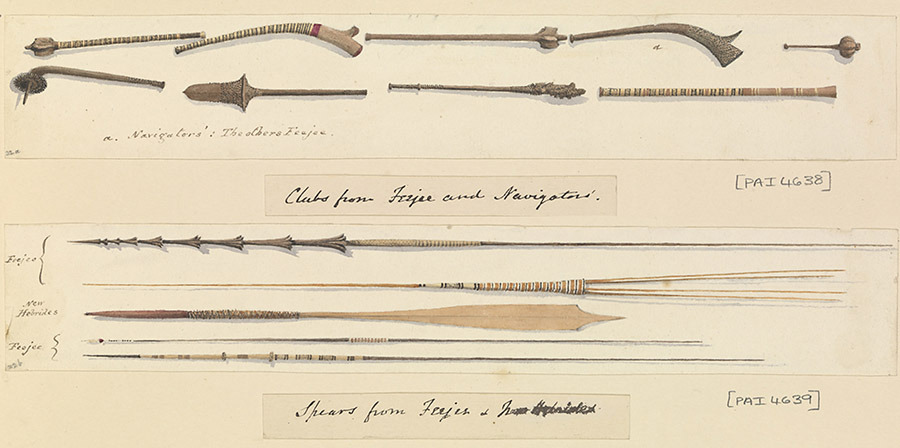

Above: A 0.75-inch caliber flintlock musket, known as a “Brown Bess.” These were the standard long guns of the British Empire’s land forces from 1722 until 1838 and would have most likely been the type of weapon with which Savage was armed. Below, Fijian weapons from the same time period. It was little wonder that the encounter ended the way it did. (Drawings from the Pacific Album, 1849–52, by Admiral Edward Gennys Fanshawe, Commander-in-Chief, Royal Navy North American Station. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London).

Savage became an important force in Fiji, where he entered into an alliance with the chieftain of Bau Island. Other innovations Savage introduced were the construction of arrow-proof structures which were used by his native allies to enforce their rule upon the islands. (Samuel Patterson, Narrative of the Adventures and Sufferings of Samuel Patterson, Palmer, Massachusetts, 1817.)

Geographic Knowledge

Another significant advantage Europeans had over the nonwhite races of the time was the scientific ability of precise navigation. The vast majority of the nonwhite races—with the exception of the Chinese, the Japanese, Semites, and certain Central American tribes—had no written languages, writing or reading ability, and were thus simply not in possession of any ability to develop charts, cartography, or any navigational capacity.

In contrast, the European use of portolan charts, Mercator projections, advanced star charts, and detailed coastal maps allowed for precise navigation.

Modern compasses had been developed in Europe during the 14th century, when the long-known practice of floating needle compasses was replaced by a “dry” compass (where the needle was mounted on a pivot, making it far more accurate and stable). The development of the “compass rose”—by the early Portuguese explorers—which added the cardinal directions of North, East, South, and West, and degrees between, was another significant advantage.

The European possession of astrolabes—mechanical devices which kept track of time and celestial bodies—enabled the White sailors to determine their direction and latitude even when out of sight of land, while chronometers allowed for precise timekeeping, which was crucial for determining longitude.

VESPUCCI WORLD MAP OF 1526: UNPARALLELED EUROPEAN GENIUS

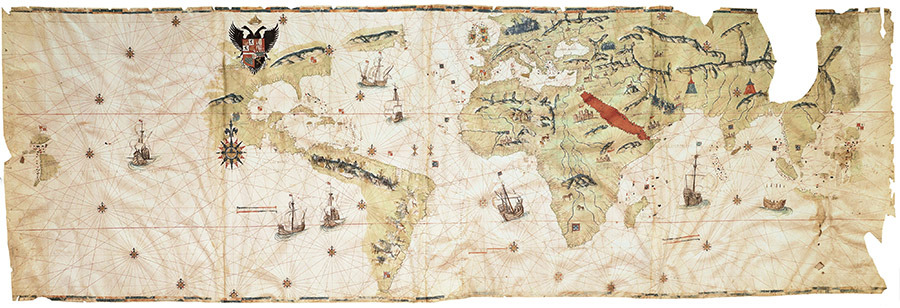

Above: Compiled by Juan (Giovanni) Vespucci, nephew of Amerigo Vespucci and Pilot Major of Spain, this map reflects the state of global geography as Europeans understood it in the early 1500s. It was assembled from the reports and sea charts of Iberian and other explorers who surveyed newly reached coasts. Navigation and mapping were accomplished through a combination of instruments and methods. Mariners relied on the magnetic compass to establish bearings, though it was subject to local variation, and on dead reckoning, which involved estimating position by recording speed with the log and line, keeping time with sandglasses, and noting the direction sailed. Celestial navigation played a central role as well, with latitude determined by means of the astrolabe or the cross-staff, instruments used to measure the altitude of the Sun at noon or the Pole Star at night. Cartographers also drew on the portolan tradition, in which rhumb lines radiated from compass roses to plot courses between ports. Alongside these charts, pilot books or rutters provided written sailing directions, distances, and hazards, supplementing visual maps with practical guidance. The Vespucci map represents not a single voyage but a synthesis of empirical seamanship, astronomical observation, and cartographic compilation. It is a tribute to the combined European genius of the time, their technology, science, and learning, all of which were without parallel anywhere else in the world. This learning and genius gave Europeans an impossible-to-beat advantage over all other races on earth, including the highly advanced Chinese and Japanese of the time. (Vespucci Map, Hispanic Society Museum & Library, Washington Heights, Upper Manhattan, New York City).

Organizational Advantages

The White races also possessed a major advantage in their self-developed day-to-day organizational ability. This ability allowed for the near-overnight erection of forts, buildings, and other structures, events which left the majority of nonwhites in awe, as most of them had advanced little beyond mud or straw huts (with the important exceptions once again of China, Japan, and some Central American tribes).

In southern Africa, for example, the Dutch settlers who landed at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652, under the command of Jan van Riebeeck, took less than 30 days to construct a large wooden fort to provide shelter and defense for the 98 Europeans. The Khoi natives, called “Hottentots” by the Dutch, were astonished to witness the erection of the fort, as they had never seen or built any sort of structure that large.

This pattern would be repeated in the Americas, Australia, New Zealand, and many parts of Asia. In all these regions, the ability of a small group of European settlers to quickly erect large buildings would overawe the natives time and time again.

Societal Advantages

In addition, the European possession of many day-to-day items was the by-product of their civilizational superiority. These items played no direct role in the conquest or the establishment of European colonies, but served to imbue the nonwhite tribes of Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and many parts of North and South America with the idea that Whites simply had better standards of living and were therefore “superior.”

These items included simple things such as cooking utensils and food preservation techniques; iron and copper pots which were clearly more practical and durable than those made of clay; axes (the feared “tomahawk” of the North American Amerindians was copied from the European axe); saws, hammers, and even simple items like nails—all provided technological and cultural revolutions to the nonwhites.

Many early explorers were, for example, able to trade with the natives by simply offering them iron nails in exchange for fresh fruit or meat.

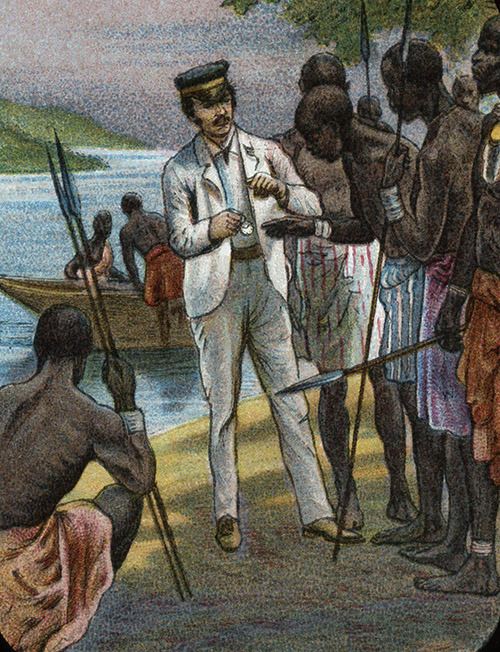

DAVID LIVINGSTONE SHOWS A WATCH TO AFRICANS, CIRCA 1850

Above: Scottish missionary David Livingstone (1813–1873), who explored Africa for over 32 years, from 1841 until his death in 1873, shows a watch to Africans in central Africa, circa 1850. This was a particularly pointless exhibition at the time, as Africans had no concept of timekeeping. Even this image is inaccurate, as the Africans at that time would not have possessed the colored material clothes around their waists—this was a detail added to spare the modesty of the Victorian-era viewers of this 1900 illustration. Livingstone’s diaries also revealed that the wheel was completely unknown in Africa prior to his travels, with his 1851 visit to the village of Linyati (in present-day Malawi) being particularly notable when the entire village turned out to see the wheels on his wagon. (Glass magic lantern slide, circa 1900, Item D18391, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK).

Wheel Non-existent in Much of the New World

It should also be noted that, at the time of the European exploration of North and South America, Sub-Saharan Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and many Asia-Pacific islands, the native tribes were not even in possession of the wheel.

The total absence of this device, which is the basis of almost all technological advancement, meant that those nonwhites were unable to progress beyond the most basic technological levels by themselves.

Without the wheel, any sort of progress was impossible. It is impossible to turn wood or stone, or in fact create any sort of technology, without the wheel, and the failure of so many nonwhite races to develop even this most basic stepping stone of civilization helped cement in the minds of European explorers that they were dealing with what they called “primitive races.”

The appearance of Europeans in such a world must have had the impression of supernatural forces appearing in the natives’ lives, and this was indeed what many nonwhite tribes believed at the time, as recorded by the early European explorers.

In the famous diaries made by the Scottish explorer David Livingstone (1813–1873), for example, he makes mention of the entire population of the village of Linyanti (located in present-day Malawi) being overawed by the wheels on his carts:

“The whole population of Linyanti, numbering between six and seven thousand souls, turned out en masse to see the wagons in motion. They had never witnessed the phenomenon before. . .” (Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, David Livingstone, Chapter 9, p. 178, London, John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1857.)

Livingstone also recounted remarks made to him by a “rainmaker” of a central African tribe about the technological gap between the races:

“Truly! but God told us differently. He made black men first, and did not love us as he did the white men. He made you beautiful, and gave you clothing, and guns, and gunpowder, and horses, and wagons, and many other things about which we know nothing. But toward us he had no heart. He gave us nothing except the assegai, [a spear] and cattle, and rain-making. . .” (Ibid., Chapter 1, p. 24.)

Europeans Write Down Nonwhite Languages

In addition to these and many other all-encompassing technological differences, the Europeans were immediately placed in a position of cultural dominance through their possession of written language. A race which does not have a written language is at a disadvantage that cannot be overcome: without writing, it is impossible to create or maintain any sort of cultural, intellectual, or historical record.

Before the Age of Exploration, for example, all Indian tribes of North America had no form of written language, along with the Inuit (“Eskimos”) of the Arctic regions.

In Central America, the Pueblo tribes (the Hopi, Zuni, Taos, Acoma, Laguna, etc.), along with the Taino of the Caribbean (Cuba, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Jamaica), the Carib and Arawak peoples of the Lesser Antilles and coastal South America, and the Chorotega of Nicaragua and Costa Rica also had no written language.

In South America, the Mapuche of Chile and Argentina, the Guaraní of Paraguay, Brazil, and Argentina, the Tupi of coastal Brazil, the Yanomami of the Brazilian and Venezuelan Amazon rainforest, the Jivaro of Ecuador and Peru, and the Kayapo and Bororo tribes of Brazil were also illiterate.

In Africa, all the Bantu-speaking peoples of Sub-Saharan Africa had no writing: this included the Zulu and Xhosa of South Africa, the Maasai of Kenya and Tanzania, the San (Bushmen) of Southern Africa, the Himba of Namibia and Angola, the Ewe of Ghana, Togo, and Benin, and the Hausa of Nigeria and Niger.

In Asia, numerous Siberian groups such as the Evenki, Chukchi, and Nenets, along with Mongolic and Turkic nomadic tribes of Central Asia, were illiterate. The Dayak tribes of Borneo in Indonesia and Malaysia, along with the Toraja of Sulawesi, Indonesia, were also illiterate.

In Australia and the Pacific Islands, the Australian Aborigines, the Māori of New Zealand, the Samoans, Tongans, and Fijians also possessed no written language.

In all of these cases, the written languages these people possess today are the result of Europeans writing them down. As this process was often undertaken by classically trained missionaries, these languages were often “given” a grammatical structure with declensions and forms based on Latin—refinements which did not exist in the original spoken form.

In Africa, for example, Swahili (the dominant language in northeast Sub-Saharan Africa) was first compiled and written down by German missionary Johann Ludwig Krapf. It was he who, in 1850, published Outline of the Elements of the Kiswahili Language, the very first Swahili grammar book.

In southern Africa, the Zulu language was first committed to writing by a collaboration between the American missionaries Newton Adams, George Newton, and Aldin Grout. In 1838 they produced the first written Zulu work Incwadi Yokuqala Yabafundayo (“The First Book for Students”).

The Xhosa language—perhaps best known as being the home language of South Africa’s African National Congress leader Nelson Mandela—was first committed to writing in 1823 by Scottish missionaries John Ross and John Bennie at the Lovedale Mission Station.

In addition, the Whites had to invent words for concepts foreign to Africans. For example, as the wheel was completely unknown in Sub-Saharan Africa, the early missionaries who wrote down the African languages had to invent a new word for “wheel.”

In Xhosa, one of the most widely spoken African languages in Southern Africa, the word for “wheel” is ivili, a corruption of the Dutch word wiel and the English word wheel.

In Australia, the Aboriginal language was first written down by English Lieutenant William Dawes, an astronomer and linguist with the British “First Fleet” of 1788. He captured the sounds as best he could and wrote them down in a series of notebooks from 1790 to 1791. His notations still form the basis of the Aboriginal written language.

NONWHITE LANGUAGES WRITTEN DOWN BY WHITE MISSIONARIES

The absence of writing in many parts of the New World served as a further indication of the vast cultural gap between the races. Above left, Johann Ludwig Krapf (1810–1881), a German missionary who was the first to write down the major African language in East Africa, Swahili. In 1850, he published Outline of the Elements of the Kiswahili Language, the first Swahili grammar book; center, the American missionary Newton Adams (1804–1851), who was one of a set of three Americans who first wrote down the Zulu language in southeastern Africa, and who co-authored Incwadi Yokuqala Yabafundayo, (“The First Book for Students”) the first written book in the Zulu language; and right, Thomas Kendall (1778–1832), the Anglican missionary to New Zealand, the first to write down the Māori language, and who in 1815 published the first book in that language, A korao no New Zealand (“The New Zealander’s First Book: Being an Attempt to Compose Some Lessons for the Instruction of the Natives”), and who in 1820 collaborated with British Cambridge, UK, professor Samuel Lee to produce A Grammar and Vocabulary of the Language of New Zealand, the book upon which all Māori grammar and lexicon are based.

In New Zealand, the Māori language was first written down by the Anglican missionary Thomas Kendall, who in 1815 published A korao no New Zealand (“The New Zealander’s First Book: Being an Attempt to Compose Some Lessons for the Instruction of the Natives.”) Then, in 1820, Kendall collaborated with Professor Samuel Lee at Cambridge University in England to produce A Grammar and Vocabulary of the Language of New Zealand, a work which standardized the written form of Māori.

It is no coincidence that the races which did not have writing at all were the regions in which the notion of “white supremacy” was the most keenly felt and experienced by all parties.

Clothing Absent in Many Parts of the World

Woven clothes made of wool or linen fabrics were another innovation for nonwhites living in Africa, many parts of Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and many parts of the Americas. Even shoes and hats were a revelation to many nonwhites.

In the journals of British explorer Captain James Cook (1728–1779), for example, he noted that during his visit to Easter Island in 1774, the natives there would literally steal the hats off the White men’s heads:

“. . . expert thieves and as tricking in their exchanges, as any people we had yet met with. It was with some difficulty we could keep the hats on our heads; but hardly possible to keep any thing in our pockets. . .” (A Voyage Towards the South Pole and Round the World, James Cook, Volume I, Chapter VII, London, William Strahan and Thomas Cadell, 1777.)

CAPTAIN COOK ATTEMPTS TO LAND AT BOTANY BAY, 1770

Above: Australian Aborigines attack the approaching crew of HMS Endeavour, commanded by James Cook, on April 29, 1770, during the first attempt by Cook to land at Botany Bay on the east coast of Australia. The naked Aborigines refused to parley with the Whites or their Tahitian guide, who attempted to communicate with them. Cook’s journals record that musket shots were fired to drive the attackers back, and after this confrontation, the British landed and collected spears, shields, and other objects, one of the most famous being the “Gweagal shield,” now in the British Museum. (Illustration from Picturesque Atlas of Australasia, Sydney: Picturesque Atlas Publishing Co., 1886–1888).

“African Clothing” Actually Arab Origin

It should be noted that some Africans in those parts of that continent which had either been colonized or settled by Arabs (as part of the great Muslim slave-trading empire, which dwarfed the Trans-Atlantic slave trade in numbers and duration) possessed items such as limited metalworking and clothing which had been imparted to them by their Arab overlords.

In this way in particular, the Africans of northeastern Africa possessed Arab-style clothing, and some African tribes possessed limited metalworking skills.

These Arab-influenced outliers aside, the reality remains that the vast majority of nonwhites in Sub-Saharan Africa, Australia, New Zealand, North America, and large parts of Central and South America possessed absolutely no technology, clothing, or civilizational advancements which were even remotely comparable to those which the White explorers and colonials possessed.

Descriptions of Australian Aboriginals

The encounter with the Bardi people of the northwest coast of Australia in 1688 by British explorer William Dampier (1651–1715) was one of the first recorded interactions between Europeans and the indigenous peoples of Australia.

Dampier described the Bardi tribe as the most “miserable” and “primitive people in the world,” and remarked upon their total lack of clothing, that they had almost no possessions at all, and that the most sophisticated tools they had were stones. (A Voyage to New Holland etc. in the Year 1699, Captain William Dampier, London, James and John Knapton, 1729.)

The explorers George Bass (1771–1803) and Matthew Flinders (1774–1814) provided a detailed description of the Dharawal Aborigines during their exploration of the coastline south of Sydney.

Noting that the Aborigines were mostly naked except for some who wore a kangaroo skin cloak over their shoulders, the explorers made specific mention of the lack of any seafaring craft or ability:

“None of the small islands had been visited, no canoes were seen, nor was any tree found in the woods from which the bark had been taken for making one. They were fearful of trusting themselves upon the water. . .” (A Voyage to Terra Australis Undertaken for the Purpose of Completing the Discovery of that Vast Country, Matthew Flinders, Chapter III, Volume I, London, G. and W. Nicol, 1814.)

In addition, the explorers noted they were completely unable to make the Aborigines understand what or how something as simple as a fishhook worked:

“. . . we could never succeed in making them understand the use of the fish hook, although they were intelligent in comprehending our signs upon other subjects.” (Ibid.)

Flinders was also one of the first explorers to point out the massive superiority which the Whites possessed over the nonwhites:

“The manners of these people are quick and vehement, and their conversation vociferous, like that of most uncivilised people. They seemed to have no idea of any superiority we possessed over them; on the contrary, they left us, after the first interview, with some appearance of contempt for our pusillanimity; which was probably inferred from the desire we showed to be friendly with them. This opinion, however, seemed to be corrected in their future visits.” (Ibid.)

The explorers also remarked about the weapons of the Aboriginals as follows:

“Of bows and arrows not the least indication was perceived, either at these islands or at Coen River; and the spears were too heavy and clumsily made, to be dangerous as offensive weapons: in the defensive, they might have some importance.” (Ibid., Chapter IV, Volume II.)

When Bass and Flinders reached Sandy Cape, off the coast of Queensland, Australia, they noted that the Aboriginals were “entirely naked,” and they had this in common with Aborigines “in any part of Terra Australis.”[(Ibid., Chapter I, Volume II.)

Descriptions of New Zealand Māoris

James Cook led three voyages to the Pacific, mapping vast regions, including New Zealand. During his first voyage (1769–1770), he circumnavigated and mapped North and South Island, and his accounts, based on multiple landings, provide detailed observations of the Māori:

“The people are of a strong, robust, and active make, taller than the common size of Europeans, and their colour is a dark brown . . . Their hair is black and straight, sometimes tied up in a small knot on the crown of their heads . . . They paint their faces with a red ochre mixed with oil, and their bodies are tattooed with black lines in spiral and other figures . . . Their dress consists of a mat made of flax, thrown over their shoulders, leaving the breast and arms bare, and a short skirt of the same about their waists.” (A Voyage Towards the South Pole, and Round the World, Vol. I, James Cook, London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1777.)

PRE-NEOLITHIC MĀORI LIFESTYLE BEFORE EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT

Above: Two Māori tribesmen are shown in their natural environment before the arrival of White people. This accurate representation is displayed in a photograph taken at the Māori life diorama in the Canterbury Museum, Wellington, New Zealand.

The French navigator and explorer Jean-François-Marie de Surville (1717–1770) reached New Zealand around the same time as James Cook, and provided the following description of the Māori:

“The savages of this country are tall, vigorous, and well-proportioned, with a skin colour between olive and black . . . Their hair is black and tied up in a tuft, adorned with feathers . . . They wear little clothing, only a sort of mat woven from plants that covers their shoulders and a small piece tied around the middle, leaving the rest of their bodies bare . . . Their faces and bodies are marked with lines drawn in black, which they seem to regard as a mark of distinction.” (“Voyage de Surville dans l’Océanie,” Jean-François-Marie de Surville, first published in 1783 as part of the book Nouveau Voyage à la Mer du Sud, commencé sous les ordres de M. Marion, “New Voyage to the South Sea, begun under the orders of M. Marion,” by Julien Marie Crozet. Translated into English in Early Eyewitness Accounts of Maori Life, edited by John Dunmore, Wellington: New Zealand Electronic Text Centre, 1984.)

French explorer Marion du Fresne (1724–1772), who led expeditions in the Indian and Pacific Oceans and was killed and eaten by Māori tribesmen in 1772, described the Māori as follows in the year of his death:

“These people are of good stature, robust, and of a reddish-brown complexion… Their hair is long, black, and gathered into a topknot with feathers inserted… Their clothing is scanty, consisting of a mat of flax fibre thrown over one shoulder and a small girdle about the loins, leaving most of their bodies exposed… They decorate their faces with intricate black markings, which they make with a sharp tool, and they carry clubs and spears of wood, hardened in the fire.” (Nouveau voyage à la mer du Sud, commencé sous les ordres de M. Marion, capitaine des vaisseaux du roi, et achevé, après la mort de cet officier, sous ceux de M. le Chevalier Duclesmeur, garde de la marine, Julien Crozet, Paris, Chez Barrois l’aîné, 1783. Translated into English as Crozet’s Voyage to Tasmania, New Zealand, the Ladrone Islands, and the Philippines in the Years 1771–1772, London, Truslove & Shirley, 1891.)

Descriptions of North American Indians

When the famous explorer Christopher Columbus (1451–1506) arrived in the Americas during his 1492–1493 voyage, he described the Indians of the Bahamas and Greater Antilles as follows:

“They all go naked, men and women, as their mothers bore them… They have no iron or steel or weapons, nor are they fitted to use them…” (“The Diario of Christopher Columbus’s First Voyage to America, 1492–1493,” edited by Bartolomé de las Casas and first published in Martín Fernández de Navarrete’s Colección de los viajes y descubrimientos que hicieron por mar los españoles desde fines del siglo XV, “Collection of the Voyages and Discoveries Made by the Spaniards by Sea Since the End of the 15th Century,” Volume 1, Imprenta Real, Madrid, 1825.)

The famous French explorer Jacques Cartier (1491–1557), while exploring the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the St. Lawrence River, encountered Mi’kmaq and St. Lawrence Iroquoians in what is today Canada, and provided this description of their attire:

“They wear their hair tied up on top of their heads like a handful of twisted hay… They go wholly naked except for a small skin about their loins, with which they cover their privy parts, and some old skins cast about their shoulders.” (Brief récit et succincte narration de la navigation faite en MDXXXV et MDXXXVI, Jacques Cartier, 1545, France. Translated into English as A Short and Brief Narration of the Navigation Made in 1535 and 1536, and first published in 1580 in England.)

AMERICAN INDIANS, EAST COAST, 1585

Above: A watercolor painting of Secotan Indians made in 1585 by the English colonial governor, explorer, and artist John White (c. 1539–c. 1593). White was part of the first attempt to colonize Roanoke Island in 1585, where he served as mapmaker for the expedition. He returned to England and then served as governor of the second attempt to found Roanoke Colony after the first settlers had vanished. He made watercolor sketches of the local Indians, the first such eyewitness paintings ever made. (British Museum, Print Room, London).

The Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto (c. 1500–1542), most famous for leading the first European expedition deep into the southeastern United States, including the discovery of the Mississippi River, encountered the Timucua, Apalachee, and Chickasaw tribes. His chroniclers recorded detailed observations of the attire of those tribes:

“The Indians came forth in their canoes… all naked, painted with red ochre and other colors, with feathers of many hues on their heads, and great pieces of skin hanging from their waists. . . The women wear a kind of deer-skin petticoat down to their knees, and the men go naked save for a breechcloth, though the caciques [chiefs] wear cloaks of marten skins.” (Relaçam verdadeira dos trabalhos que ho governador dom Fernando de Souto e certos fidalgos portugueses passaram no descobrimento da provincia da Florida, 1557, commonly translated as A True Relation of the Hardships Suffered by Governor Hernando de Soto and Certain Noble Portuguese in the Discovery of the Province of Florida.)

The Italian explorer Giovanni Caboto (c. 1450–c. 1500), also known as John Cabot, who sailed under the English flag and is credited with the first European exploration of North America’s coast since the Norse settlements, noted the attire of the Indians of what is today Canada’s East Coast as follows:

“The people of this land go naked, save for certain skins of beasts about their middles, and they paint their bodies with colors.” (Letter from John Day to the “Lord Grand Admiral” (Columbus), discovered in Spanish archives and published in Archivo General de Simancas, Valladolid, Spain, 1956. English translation in The Journal of Christopher Columbus, Cecil Jane, London: Hakluyt Society, 1960.)

The Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano (1485–1528), most famous for being the first European to explore the Atlantic coast of North America, including what is today New York Harbor, told of his sightings of the Algonquian-speaking Indian peoples as follows:

“They go entirely naked except that around their loins they wear skins of small animals like martens, with a narrow belt of woven grass and tails of other animals hanging down… The women are dressed in the same way, though some wear a deer skin ornamented with great artifice . . . In the north, they wear skins of bears, wolves, and deer, roughly sewn together, covering their bodies more fully against the cold.” (Letter to King Francis I of France, written July 8, 1524, first published in Italian in Raccolta di Documenti e Studi by Ramusio, Venice, Italy, 1556. English translation in The Voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano, Lawrence C. Wroth, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970.)

The Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (c. 1490–c. 1559), best known for being one of the survivors of the ill-fated Narváez expedition (1527–1536), published his account of the Indians of the Gulf Coast and Southwest and described them as follows:

“They go naked all year, except the women who cover their privates with a kind of moss or deer skin… The men wear nothing but a small piece of hide over their loins.” (La Relación, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, 1542, Zamora, Spain, de Paz and Picardo. Translated into English as The Account: Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s Relación, 1993, Arte Público Press.)

Descriptions of Central and South American Indians

In strong contrast to the descriptions of natives elsewhere in the world, the early White explorer journals reported freely on the fact that the Aztecs and Incas of Central and South America possessed woven clothing.

The fact that the explorer journals made specific mention of these clothes disproves allegations that the colonial-era Whites set out to portray all nonwhites as “inferior” in their writings. The existence of such records serves to confirm that the Whites merely wrote down what they saw, and this was quite separate from any notions of “white supremacy” which emerged later.

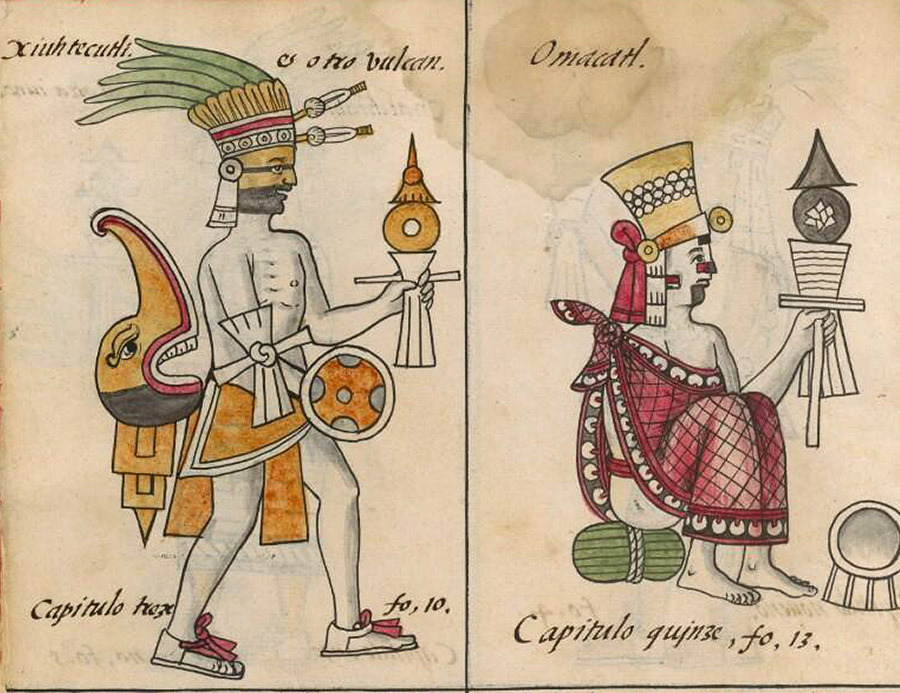

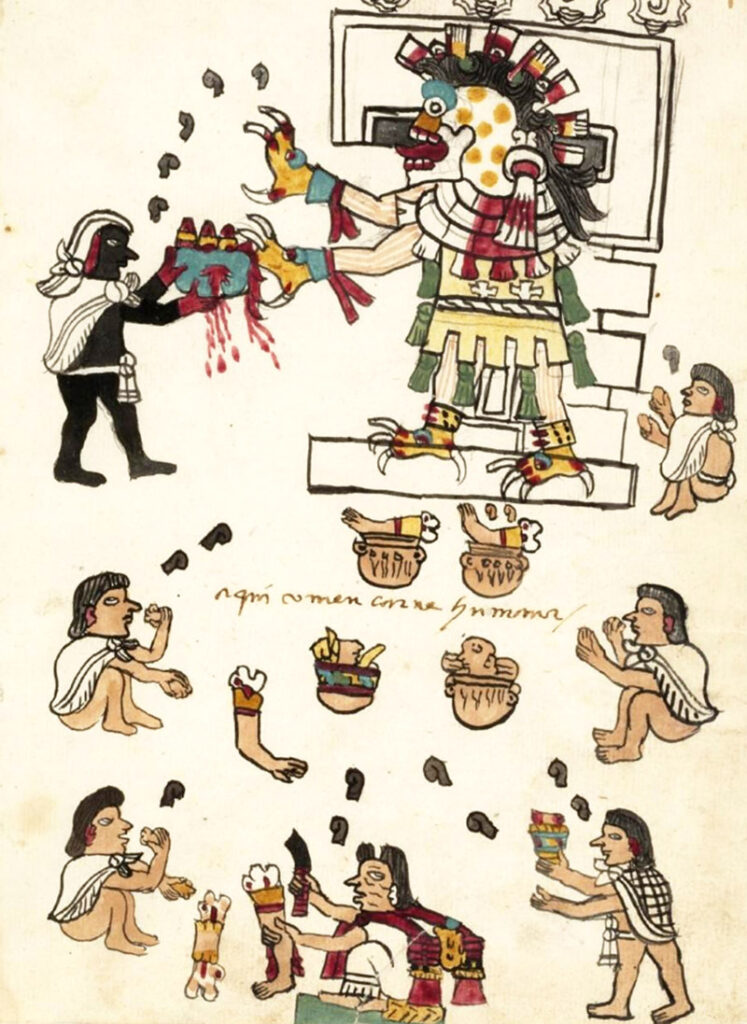

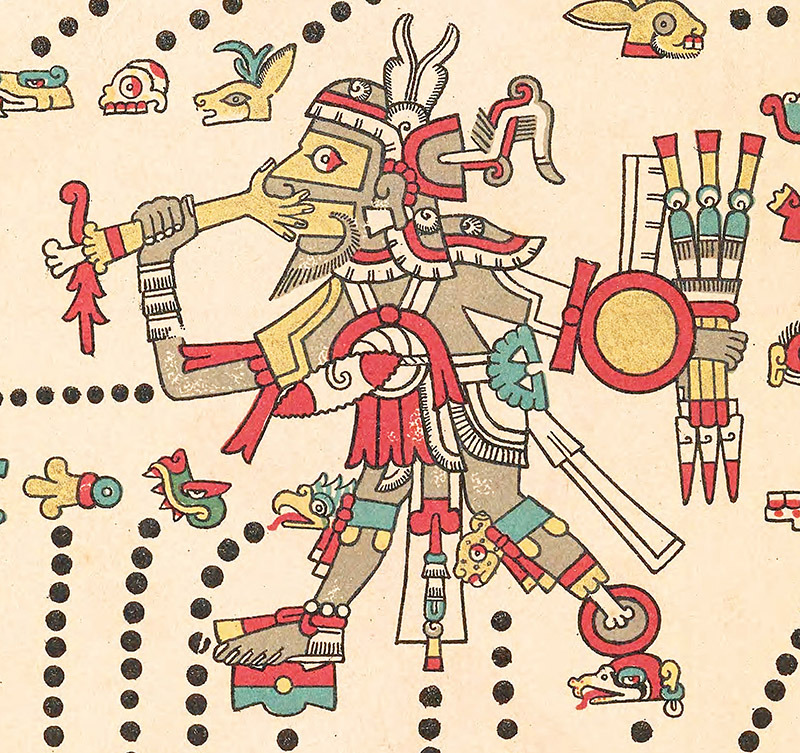

AZTEC CLOTHING, 1577: FLORENTINE CODEX

Above: Aztec clothing, as depicted in the 1577 Florentine Codex, created by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún and a group of Aztec Nahua elders, authors, and artists. Written in parallel columns of Nahuatl and Spanish texts and hand-painted with nearly 2,500 images, the codex is the most reliable source of information about the Aztec Empire. When it was completed at the Imperial Colegio de la Santa Cruz in Tlatelolco (today Mexico City), the manuscript was sent to Europe, where it was purchased by the Medici family library in Florence, and hence its name. (Book 2, Calendar and Festivals, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Italy.)

For example, the soldier under Conquistador Hernán Cortés, Bernal Díaz del Castillo (1492–1584), who documented the conquest of Mexico, wrote of the Aztecs:

“The Mexicans who accompanied us told us that it was the great Montezuma who was coming to meet Cortés… He was richly dressed, according to their customs, and wore a kind of crown of gold and feathers on his head, with a plume of green feathers, and he had on a mantle of fine cotton embroidered with many colors, and breeches of the same material, and sandals of a kind they call cactli, made of gold and precious stones.” (Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Madrid, Spain, Alonso Remón, 1632. Translated as The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico, by A.P. Maudslay, New York: Farrar, Straus and Cudahy, 1956.)

Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), the Spanish conquistador who led the expedition that resulted in the fall of the Aztec Empire and the colonization of Mexico for Spain, described Aztec attire in this way:

“The people of this city [Tenochtitlan]… dress in cotton garments, very well made, and the lords wear over these cloaks of very fine workmanship, adorned with feathers and precious stones . . . The women wear skirts and tunics of cotton, very finely woven, and some cover themselves with veils like Moorish women.” (“Second Letter to Charles V,” October 30, 1520, Letters from Mexico, translated by Anthony Pagden, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.)

The Spanish historian and priest, Francisco López de Gómara (1511–c. 1566), known for his works on the Spanish conquest of the Americas, compiled eyewitness accounts of the campaign led by conquistador Francisco Pizarro (c. 1478–1541), who conquered the Inca Empire and claimed much of South America for Spain. De Gómara described the Incas as follows:

“The Indians of Peru wear tunics of cotton or wool, according to their station, and the lords have them dyed in many colors, with fine cloaks over their shoulders, and on their heads they wear caps or cords of wool, signifying their rank… The women also wear long dresses that reach the ground, fastened with belts of gold or silver.” (La Historia General de las Indias y conquista de México, Francisco López de Gómara, Zaragoza, 1552. Translated into English as Cortés: The Life of the Conqueror by His Secretary, by Lesley Byrd Simpson, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1964.)

Other tribes in Central and South America were, however, notably different from the Incas and the Aztecs. Christopher Columbus, for example, noted of the Indians living in the Caribbean (and specifically the present-day Bahamas, Cuba, and Hispaniola—the latter being the site of the first European colony in the Americas):

“They all go about as naked as their mothers bore them; and also the women, although I didn’t see more than one who was really young. And all that I saw were young people, none older than thirty years… They have no iron or steel or weapons, nor are they capable of using them.” (Carta a Luis de Santángel, “Letter to Luis de Santangel,”Christopher Columbus, February 15, 1493, first published in Barcelona, April 1493. Translated into English in Christopher Columbus, The Four Voyages, by J.M. Cohen, London: Penguin Classics, 1969).

SOUTH AMERICAN INDIANS, 1900

Above: The dramatic contrast in clothing—or rather the lack thereof—of other Indians in South and Central America with that of the Incas, the Mayas, and the Aztecs is vividly demonstrated in this 1900 photograph of Brazilian rainforest Indians. Despite over 500 years of contact with Europeans, even at that late stage the Indians were still as naked as at the time of the Age of Discovery. (“Across South America in a Warship,” Edward H. Coleman, Ainslee’s Magazine, Volume 5, February 1900, Howard, Ainslee & Co., Street & Smith, New York.)

The Italian explorer and cartographer, Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512), whose name was given to the Americas after his voyages demonstrated that the New World was a separate continent from Asia, wrote the following description of the natives of Brazil:

“They go all naked, both men and women, without covering any part of their bodies; and just as they come from their mothers’ wombs, so they go until death… They have no cloth, either of wool, linen, or cotton, because they need it not; nor have they any possessions of their own.”(“Letter to Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici,” 1501, Mundus Novus, or “New World,” Amerigo Vespucci, 1502, various cities in Europe. Translated into English in The Letters of Amerigo Vespucci, by Clements R. Markham, London: Hakluyt Society, 1894).

The Spanish explorer, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (1478–1557), after taking part in several expeditions to the Americas, was appointed as the official historian by the Spanish king to document all the early conquests in Hispaniola, Cuba, and other parts of the New World. In his remarks on the tribes of the Caribbean, he wrote:

“These Indians go about naked, save that some of the women wear a small covering of cotton or leaves over their private parts, but the men cover nothing, and they paint their bodies with red and black dyes, thinking it a great beauty.” ((Historia General y Natural de las Indias, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, 1535, Juan Cromberger, Seville. Translated into English as Natural History of the West Indies by Sterling A. Stoudemire, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1959).

The Spanish explorer, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (c. 1490–c. 1559), best known for being one of the survivors of the ill-fated Narváez expedition (1527–1536), a failed Spanish attempt to colonize Florida, described the natives of what is today Brazil as follows:

“The people we found here go naked, except that the women cover their private parts with a kind of grass or moss that grows like hair, and the men have no shame in showing all their bodies… They have no other adornment but paint and some shells they hang about their necks.” (La Relación, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, 1542, Zamora, Spain, de Paz and Picardo. Translated into English as The Narrative of Cabeza de Vaca, by Rolena Adorno and Patrick Charles Pautz, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003).

The French explorer, Protestant missionary, and writer Jean de Léry (1536–1613), lived among the Tupinambá tribe in the 1550s in what is today coastal Brazil. He confirmed the total lack of clothes among the natives, writing:

“Both men and women go entirely naked, without ever covering any part of their bodies… They shave their heads in certain places and adorn themselves with feathers and paint, but as for clothing, they have none, neither of cotton nor of any other material, and seem to feel no shame in this state.” (Histoire d’un voyage fait en la terre du Brésil, autrement dite Amérique, “History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, Otherwise Called America,” Jean de Léry, 1578, La Rochelle. Translated into English as History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil, by Janet Whatley, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990).

Descriptions of Natives of Western Africa

The Portuguese navigator Diogo Gomes (c. 1420–c. 1500), who explored parts of West Africa from the 1450s to the 1460s, provided descriptions of the Africans of the region today known as Senegal and Gambia, as follows:

“The men go naked, save for a small piece of leather or cloth about their loins, and the women wear a strip of cotton tied around their middles, leaving their breasts bare… They adorn themselves with beads and shells, but have no other garments.” (Crónica dos Feitos de Guiné, Visconde de Santarém, from the transcript prepared by Martim de Azurara, 1841, Lisbon. English translation in The Voyages of Cadamosto and Other Documents on Western Africa in the Second Half of the Fifteenth Century, edited by G.R. Crone, London: Hakluyt Society, 1937).

The Venetian explorer, Alvise Cadamosto (1432–1488), while in the service of the Portuguese, led several expeditions along the West African coast from 1455 to 1456. He confirmed Gomes’s observations, saying that:

“These negroes go all naked, except that the men wear a small piece of cotton cloth or leather to cover their privy parts, and the women have a strip of cotton cloth tied about their hips, which scarce reaches to their knees… They paint their bodies with white and red colors, and wear necklaces of shells.” (“Navigazione di Alvise da Ca’ da Mosto,” Alvise Cadamosto, Venice, 1507, as published in the Paesi Nuovamente Retrovati by Fracanzano da Montalboddo. English translation in The Voyages of Cadamosto and Other Documents on Western Africa in the Second Half of the Fifteenth Century, edited by G.R. Crone, London: Hakluyt Society, 1937).

The Portuguese explorer Duarte Pacheco Pereira (c. 1460–1533) wrote about West Africa (modern Ghana to Nigeria) based on his voyages in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, as follows:

“The people of this land go naked, both men and women, save for a small cloth of cotton or palm leaves about their privy parts… Some women wear a band of cloth around their waists, but it covers little, and their bodies are marked with scars and colors.” (Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis, circa 1506–1508, first published in 1892, Lisbon, by the Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, edited by Raphael Eduardo de Azevedo Basto. English translation in Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis, by Duarte Pacheco Pereira, translated by George H.T. Kimble, London: Hakluyt Society, 1937).

One of the earliest descriptions of Africans in present-day Guinea comes from the Portuguese navigator Fernão do Pó (c. 1440–c. 1490), most famous for exploring the Gulf of Guinea. In 1472, he noted the following:

“The inhabitants are negroes, very wild and savage, and they live in a state of nature, without towns or order.” (“Relação das Viagens de Fernão do Pó,” cited in Portuguese Voyages, 1498–1663, edited by Charles David Ley, London: J.M. Dent, 1947).

The Berber-Andalusian Leo Africanus (c. 1494–c. 1554), who was a Moroccan captured by Christians and later employed by Pope Leo X, described sub-Saharan West Africa (modern Mali, Niger) based on his pre-capture travels in the early 16th century, as follows:

“The negroes of the kingdom of Tombuto [Timbuktu] wear no clothing but a piece of cotton cloth about their loins, and the women have a cloth tied around their hips, leaving their upper parts bare.” (Descrittione dell’Africa, Leo Africanus, 1550, Venice, as contained in the work Navigationi et Viaggi, by Giovanni Battista Ramusio. English translation in The History and Description of Africa, translated by John Pory, London: Hakluyt Society, 1896, 3 volumes).

Descriptions of Natives of Southwestern Africa

The first European explorer to reach India by sea via the Cape of Good Hope at the southernmost point of Africa, Vasco da Gama (c. 1460–1524), encountered the natives of the Cape of Good Hope—who were not Africans, but what are now called Khoikhoi (and were then called Hottentots)—and described them in 1497 as follows:

“They went naked, save for a small piece of skin about their privy parts, and some had cloaks of skins thrown over their shoulders, made of the hides of beasts they hunt.” (Roteiro da Primeira Viagem de Vasco da Gama, “Journal of the First Voyage of Vasco da Gama”, Álvaro Velho, 1838, Lisbon, Diogo Köpke and António da Costa Paiva. English translation in A Journal of the First Voyage of Vasco da Gama, 1497–1499, translated by E.G. Ravenstein, London: Hakluyt Society, 1898).

Da Gama’s observations were confirmed by the Portuguese captain António de Saldanha (c. 1460–c. 1535), who is famous on two accounts: being the first European to anchor in Table Bay, Cape Town, and for exploring the southwestern coast of present-day South Africa after being separated from his fleet. Writing in the year 1503, he described the Hottentots he encountered thus:

“These blacks go all naked, except for a small skin of a beast tied about their loins, and sometimes a mantle of skins cast over their shoulders… The women wear a piece of hide like an apron before their privy parts.” (Décadas da Ásia, João de Barros, Volume I, 1552, Lisbon. English excerpts in Theal’s Records of South-Eastern Africa, Volume I, edited by George McCall Theal, Cape Town: Government of the Cape Colony, 1898).

The Dutch colonial administrator and founder of the first settlement at Cape Town, present-day South Africa, Jan van Riebeeck (1619–1677), also confirmed Da Gama’s observations on the Hottentots in 1652:

“These Hottentots go almost naked, wearing only a small skin about their privy parts, and sometimes a cloak of sheep or seal skin cast over their shoulders… The women wear the same, with an additional skin tied about their waists like an apron . . . Their children run about stark naked, and even the grown men and women cast off their skins in warm weather, covering only their shame.” (The Journal of Jan van Riebeeck, Vol. I, 1651–1662, first published in 1884, Cape Town, by the Van Riebeeck Society, edited by H.B. Thom. English translation in Precis of the Archives of the Cape of Good Hope: Journal, 1652–1662, edited by H.C.V. Leibbrandt, Cape Town: W.A. Richards & Sons, 1896).

It is significant that the Hottentots had not advanced at all in the more than 150 years between Da Gama’s and Van Riebeeck’s observations.

Van Riebeeck also noted the Hottentots’ desire to obtain, usually by theft, any of the accoutrements of White civilization:

“We have to keep a sharp lookout, for the natives are much inclined to steal whatever they can lay their hands on, especially iron, which they highly value for making their assegais and other tools.” (Ibid.),

Descriptions of Natives of Eastern Africa

Vasco da Gama went on to describe the Zulus along the southeastern coast of present-day South Africa in December 1497, as follows:

“At another place [near Natal], the men wore nothing but a sheath of wood or horn over their privy members, and the women had a cloth of cotton or skin tied about their waists, scarce covering their thighs.” (Roteiro da Primeira Viagem de Vasco da Gama, “Journal of the First Voyage of Vasco da Gama”, Álvaro Velho, 1838, Lisbon, Diogo Köpke and António da Costa Paiva. English translation in A Journal of the First Voyage of Vasco da Gama, 1497–1499, translated by E.G. Ravenstein, London: Hakluyt Society, 1898).

ZULUS, SOUTH EAST AFRICA, 1907

Above: A postcard from 1907 shows Zulu warriors dressed similarly as to how they would have appeared at the time of the Age of Exploration. In this picture, however, the Zulus are already showing signs of European influence: the beads of their headgear and necklaces, all the shoes, and the leather belt and buckle of the individual on the far right, are all European-origin additions to their dress. (Postcard, “Zulu Warriors,” published by A. Rittenberg, Durban, 1907.)

The Dutch merchant, explorer, and writer Jan Huyghen van Linschoten (1563–1611) provided this description of the Africans of East Africa (present-day Mozambique to Kenya) as follows:

“The blacks of this coast go naked, save for a small cloth of cotton or bark about their loins, and the women wear a piece tied about their hips, leaving their breasts uncovered… Some have skins of beasts cast over their shoulders.” (Itinerario, Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, 1596, Amsterdam. English translation in John Huighen van Linschoten: His Discours of Voyages into ye Easte & West Indies, translated by William Phillip, London: John Wolfe, 1598).

The Portuguese explorer and writer Duarte Barbosa (c. 1480–1521), best known for his detailed account of the natives of Africa’s east coast and Indian Ocean, wrote in 1517/1518 the following about the Bantu inhabitants of the southeastern African coast (that is, the Zulu and related tribes, located in present-day southern Mozambique and eastern South Africa):

“The negroes of this coast are black and well-made… They go naked, save that the men wear a small cloth or skin about their privy parts, and the women have a piece of cotton or hide tied around their waists, leaving their breasts bare… Some wear necklaces of beads or shells.” (“Livro de Duarte Barbosa,” Duarte Barbosa, 1518, first published 1812, Lisbon, as part of the Coleção de Notícias para a História e Geografia das Nações Ultramarinas, Academia Real das Ciências. English translation in The Book of Duarte Barbosa, translated by Mansel Longworth Dames, London: Hakluyt Society, 1918–1921, 2 volumes.)

The Portuguese explorer who served as the first Viceroy of Portuguese India, Francisco de Almeida (c. 1450–1510), stopped along the southeastern coast of present-day South Africa in 1505, and his chroniclers described the Xhosa tribe as follows:

“The inhabitants were black and naked, wearing only a small skin about their loins, and some had cloaks of cattle hides over their shoulders. . . The women wore skins tied about their middles, with another hanging before them like an apron.” (Relação das Armadas, “Account of the Fleets,” preserved in Portuguese archives and later published in Alguns Documentos do Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, or “Some Documents from the National Archive of the Torre do Tombo,” edited by José Ramos Coelho, Lisbon, Portugal, 1892. English excerpts in Records of South-Eastern Africa, Volume I, by George McCall Theal, Cape Town: Government of the Cape Colony, 1898.)

The Portuguese Dominican missionary João dos Santos (c. 1550–c. 1625), who worked in what is today southern Mozambique and eastern Zimbabwe, described the Shona and related tribes in 1590 as follows:

“The Kaffirs of this land go naked, save for a small skin or cloth of cotton about their loins, and the women wear a piece of cotton or hide tied around their waists, leaving their breasts and legs bare… The chiefs wear skins of leopards or lions over their shoulders.” (Ethiópia Oriental, João dos Santos, 1609, Évora, Portugal. English translation in Records of South-Eastern Africa, Volume VII, edited by George McCall Theal, Cape Town: Government of the Cape Colony, 1901.)

Cannibalism Shocks Europeans

While extremely isolated incidents of cannibalism were not unknown in European history, it was, however, regarded as abhorrent and subject to great censure, so the frequency and apparent acceptance of this practice in other parts of the world deeply shocked European explorers.

Marco Polo (1254–1324) was one of the first explorers to write about cannibalism during his travels in his book The Travels of Marco Polo (also known as Il Milione). In his accounts, he described the inhabitants of the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal as “wild beasts” who “are a most cruel generation, and eat everybody that they can catch, if not of their own race.” (The Travels of Marco Polo, Il Milione, Marco Polo, Book III, Chapter 13, “Of the Island of Angaman,” 1298, Genoa.)

He added that this was common in other parts of India and Southeast Asia, where tribes would eat their enemies as part of their customs.

Word “Cannibal” Originates with Caribbean Tribe

When the famous explorer Christopher Columbus arrived in the Caribbean in 1492, he recorded his encounter with the Taíno Indians on the islands, who described their enemies, the “Caribs,” as cannibals. Although Columbus, in his journals, made mention of this claim, he added that he had not personally seen any evidence.

However, the physician Dr. Diego Álvarez Chanca (c. 1463–c. 1515), who accompanied Columbus on his second voyage, provided the first eyewitness account of the Caribs’ cannibalism:

“In these islands where we now are, they say that there are Caribs who eat human flesh. . . We found in their houses human limbs hung up as if they were curing them like bacon, and fresh human flesh which appeared to have been recently cut . . . These people make war on the other islands and take as many captives as they can, whom they eat.” (“Carta del físico Diego Álvarez Chanca al Cabildo de Sevilla dándole cuenta del segundo viaje de Cristóbal Colón, en el cual descubrió la isla de San Juan,” or “Letter from the physician Diego Álvarez Chanca to the Council of Seville, reporting on the second voyage of Christopher Columbus, in which he discovered the island of San Juan,” Diego Álvarez Chanca, 1825, Colección de los viajes y descubrimientos que hicieron por mar los españoles desde fines del siglo XV, Martín Fernández de Navarrete.)

His observations were confirmed by the explorer Amerigo Vespucci (1451–1512), who, in 1502, described the Indians of the western Caribbean this way:

“They are a warlike people and very cruel among themselves… They eat human flesh, and especially that of their enemies killed in war; they roast it and eat it publicly in the presence of all… I saw a man who showed me by signs that he had eaten more than three hundred human bodies.” (Mundus Novus, or “New World,” Amerigo Vespucci, 1502, various cities in Europe.)

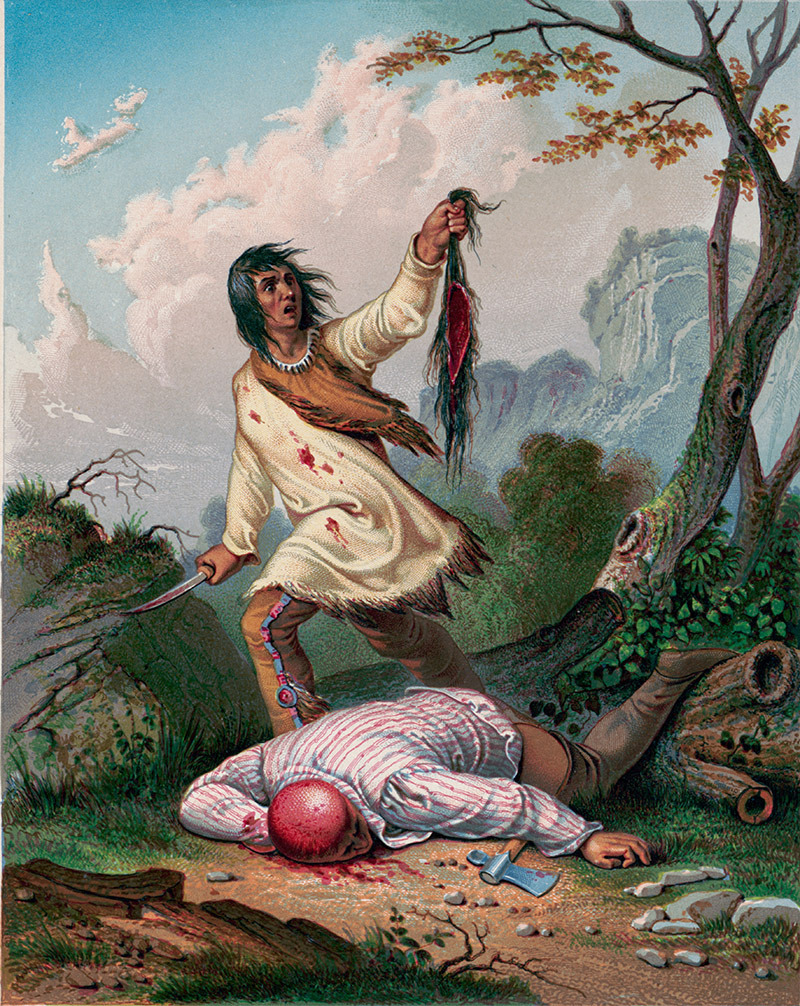

CHRISTIAN MISSIONARIES CANNIBALIZED BY CARIB INDIANS, 1516

Above: This 1850 engraving depicts the fate of a group of Franciscan friars who, in 1516, attempted to evangelize among the Indian Caribs of the Lesser Antilles. The missionaries, recently arrived from Spain, sought to establish a foothold for Christianity in the islands but were seized, killed, dismembered, and cannibalized.

The Spanish explorer Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (1478–1557), after taking part in several expeditions to the Americas, was appointed as the official historian by the Spanish king to document all the early conquests in Hispaniola, Cuba, and other parts of the New World. In his remarks on the Caribs, he said:

“The Caribs are a cruel and inhuman people, who eat human flesh, not only of their enemies but also of their own children when they lack other meat . . . They go out in their canoes to capture men and women from other islands, whom they kill and eat.” (Historia General y Natural de las Indias, Book II, Chapter 8, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, 1535, Juan Cromberger, Seville.)

In 1503, Queen Isabella of Spain issued a decree formally allowing the enslavement of cannibals in order to bring a halt to the practice in that region.

Eventually, the entire region would be named the “Caribbean” after the Carib tribe, and, after Columbus entered into his journal that the inhabitants of the “Carib island” were “Caniba,” a term he used interchangeably with “cannibals” to describe people who ate human flesh. The Spanish word caníbal evolved directly from this and entered other European languages (e.g., English “cannibal”) by the early 16th century.

Thus, the word “cannibal” comes from the name of a human flesh-eating tribe in the Caribbean Islands, the Carib tribe.

Cannibalism in Australia

The British Marine officer and author Watkin Tench (1758–1833), known for his firsthand accounts of the First Fleet and early European settlement in New South Wales, Australia, was one of the first to recount the practice of cannibalism among the Australian Aborigines, in his 1793 work A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson. Quoting a native informant, one Bennelong, Tench wrote:

“Bennelong told us, that when a man of one tribe kills one of another, and the body is not burnt or buried, the friends of the dead sometimes eat a part of it, not for want of food, but to make their hatred stronger against the killer’s people.” (A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, Watkin Tench, London, 1793, G. Nicol and J. Sewell.)

Sir George Grey (1812–1898), the British soldier, explorer, and colonial governor, known for his expeditions in Australia and for serving as Governor of South Australia, New Zealand, and the Cape Colony during the 19th century, also noted a firsthand observation of cannibalism in the aftermath of a conflict near the Gascoyne River in Western Australia:

“We came upon a spot where the natives had recently been encamped; and here I was shocked to find the roasted remains of a human arm, the bones still adhering to the flesh, which had evidently been cooked and eaten by the natives who had fled at our approach.” (Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery in North-West and Western Australia, during the Years 1837, 38, and 39, George Grey, London, 1841, T. and W. Boone.)

Edward John Eyre (1815–1901), the British explorer, colonial administrator, and pioneer known for his expeditions across Australia, including his 1840–1841 crossing of the Nullarbor Plain, reported on Aboriginal cannibalism in the Murray River region as follows:

“Among some tribes it is the custom, after a battle or murder, to eat a portion of the slain, generally the fat about the kidneys or the heart; this they do not from hunger, but from a belief that it gives them the strength and courage of the dead man.” (Journals of Expeditions of Discovery into Central Australia, and Overland from Adelaide to King George’s Sound, in the Years 1840–1, Edward John Eyre, London, 1845, T. & W. Boone.)

The Scottish-Australian explorer John McDouall Stuart (1815–1866), best known for leading the first successful south-to-north crossing of Australia in 1862, noted during his 1860 journey near the Finke River in Central Australia, evidence of recent cannibalism:

“We found a native camp abandoned, and near it the bones of a man, broken and scattered, with marks of teeth upon them, as if the flesh had been torn off and eaten; this I take to be a sign of their devouring one of their own. . .” (Explorations in Australia: The Journals of John McDouall Stuart during the Years 1858, 1859, 1860, 1861, & 1862, John McDouall Stuart, London, 1864, William Hardman.)

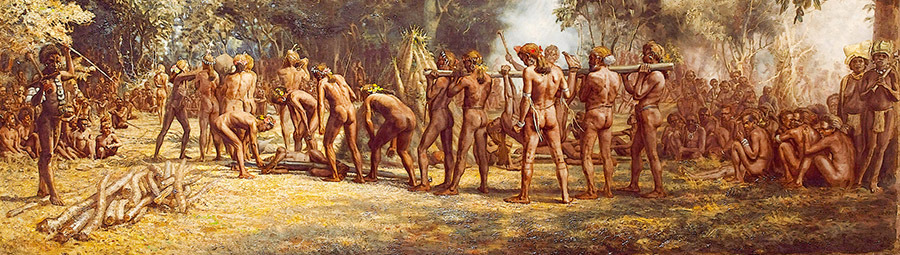

CANNIBAL FEAST, VANUATU, CIRCA 1880

Above: A cannibal feast on the island of Tanna, New Hebrides, southern Vanuatu, as captured by a visiting European in circa 1880. The victims are bound and being carried like carrion on logs, while the tribe gathers for the feast. (Cannibal Feast on the Island of Tanna, New Hebrides, Charles E. Gordon Frazer, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia).

Aboriginal cannibalism persisted until at least the late 19th century. Carl Lumholtz (1851–1922), the Norwegian explorer, ethnographer, and naturalist known for his extensive fieldwork in Australia, Mexico, and Borneo, wrote in his famous work Among Cannibals: An Account of Four Years’ Travels in Australia, published in 1888, that he had personally witnessed cannibalism in Queensland:

“I saw them prepare the body of a dead warrior from a neighboring tribe; they cut off the flesh with stone knives, roasted it over a fire, and ate it, saying that by doing so they took his spirit into themselves and kept his power from their enemies.” (Blandt Menneskeædere: Fire års Reise i Australien, Carl Lumholtz, Copenhagen, Forlagsbureauet, 1888. Published in English as Among Cannibals: An Account of Four Years’ Travels in Australia and of Camp Life with the Aborigines of Queensland, 1889, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons.)

Cannibalism in New Zealand

The French explorer Jules Dumont d’Urville (1790–1842), most famous for his discovery of the Antarctic, visited New Zealand’s South Island in 1827 and provided an in-depth description of the Māori, focusing on their cannibalism, which, he revealed, formed an integral part of their warfare:

“They [the Māori] admitted without hesitation that they eat the flesh of their enemies slain in combat; one chief, showing me the oven where they had cooked a man killed a few days before, said with a laugh that it was ‘very good eating,’ and pointed to the remains of bones still scattered near the fire.” (Voyage au Pôle Sud et dans l’Océanie sur les corvettes l’Astrolabe et la Zélée, Jules Dumont d’Urville, 1842–1846, Paris, Gide éditeur. Translated into English as An Account in Two Volumes of Two Voyages to the South Seas, by Captain (later Rear-Admiral) Jules S-C Dumont D’Urville, J. Tastu, Paris, 1832.)

The British explorer James Cook explored New Zealand’s coasts in 1769–1770. His journals include an encounter he had with Māoris during his stay in Queen Charlotte Sound, January 1770:

“They eat their Enemies whom they kill in Battle; this they told us with a kind of pleasure, and shewed us how they did it, by cutting the flesh from the bones with a sharp shell and roasting it on a fire.” (An Account of the Voyages Undertaken by the Order of His Present Majesty for Making Discoveries in the Southern Hemisphere, James Cook, London, 1773, W. Strahan and T. Cadell).

French explorer Marion du Fresne (1724–1772), who led expeditions in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, was killed and eaten by Māori tribesmen in 1772. After his death, his second-in-command, Julien Crozet (1728–1782), documented the incident:

“The savages had cut up the bodies of M. Marion and sixteen of our men, roasted them over a fire, and devoured them in our sight, with the most horrible yells and gestures.” (Nouveau voyage à la mer du Sud, commencé sous les ordres de M. Marion, capitaine des vaisseaux du roi, et achevé, après la mort de cet officier, sous ceux de M. le Chevalier Duclesmeur, garde de la marine, Julien Crozet, 1783, Paris, Chez Barrois l’aîné. Translated into English as Crozet’s Voyage to Tasmania, New Zealand, the Ladrone Islands, and the Philippines in the Years 1771–1772, London, 1891, Truslove & Shirley).

The 1809 massacre of the crew of the Boyd (as described in a later chapter) was another famous early incident of Māori cannibalism. After hearing reports of the attack, the Scottish merchant, explorer, and pioneer settler in Australia, Captain Alexander Berry (1781–1873), led a rescue mission to Whangaroa Harbour in January 1810, and his account is based on his interactions with Māori informants, including chiefs, and his observations of the aftermath:

“The natives, having thus got possession of the deck, rushed in a body upon the people who were below, knocking them on the head with their war clubs as they came up, and cutting their bodies to pieces while yet alive; after which they cooked and devoured them, making one horrible feast of the whole crew, excepting the four individuals whom they spared.” (“Account of the destruction of the ship Boyd and massacre of the Captain and crew, by the natives of Wangaroa New Zealand,” Captain Alexander Berry, first published in Constable’s Miscellany of Original and Selected Publications in the Various Departments of Literature, Science, and the Arts, Volume IV, Adventures of British Seamen, Hugh Murray, 1826, Edinburgh, Archibald Constable & Co.)

The British writer and politician Edward Jerningham Wakefield (1820–1879), best known for his role in the “New Zealand Company,” which started the colonization of that land, provided another account of Māori cannibalism, describing events near Wellington in the 1830s:

“The old chief told me with pride that in the last war with Ngatiraukawa, his people had killed and eaten more than a hundred of their enemies, roasting their flesh in the ovens and feasting for days.” (Adventure in New Zealand, from 1839 to 1844, Volume 1, Chapter 3, Edward Jerningham Wakefield, 1845.)

The British missionary, printer, botanist, and politician William Colenso (1811–1899), best known for printing the first book in New Zealand, extensively documented Māori cannibalism in his 1868 work On the Māori Races of New Zealand:

“The Maori of old would slay their enemies in battle, and then, with savage joy, cook and eat their bodies; I have heard from their own lips how they cut the flesh from the slain and roasted it, believing it made them fiercer warriors.”[53] (On the Māori Races of New Zealand, Volume 1, William Colenso, Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute, Dunedin, 1868.)

The Anglo-Irish trader, writer, and judge Frederick Edward Maning (1812–1883), best known for his works on the early history of New Zealand, lived among the Ngāpuhi from 1833, after which he wrote a semi-autobiographical account of Māori life. He describes witnessing preparations for cannibalism in the 1830s:

“The oven was heated, and the body of the slain enemy laid on the stones; they cut him up with their stone knives, and the smell of roasting flesh filled the air as they chanted their war songs.” (Old New Zealand: A Tale of the Good Old Times, Frederick Edward Maning, Chapter 8, Auckland, 1863.)

Cannibalism in New Guinea

In New Guinea, the early White explorer Jan Carstensz (?–1628), during one of the first White explorations of that region, remarked numerous times upon the cannibalistic nature of the native population, saying that:

“. . . we found to be savages and man-eaters, refused to hold parley with us, and fell upon our men who suffered grievous damage; after the report, however, of some of the men of the yacht Aernem, who being wounded on the 11th aforementioned, succeeded in making their escape, the natives are tall black men with curly heads of hair and two large holes through their noses, stark naked, not covering even their privities; their arms are arrows, bows, assagays, callaways and the like . . . the natives are coal-black like the Caffres; they go about stark naked, carrying their privities in a small conch-shell, tied to the body with a bit of string; they have two holes in the midst of the nose, with fangs of hogs or swordfishes through them, protruding at least three fingers’ breadths on either side, so that in appearance they are more like monsters than human beings; they seem to be evil-natured and malignant. . . there were also among them . . . wearing two strings of human teeth round their necks, and excelling all the others in ugliness . . . their canoes also contained a number of human thigh-bones, which they repeatedly held up to us, but we were unable to make out what they meant by this. . . During their march they [an exploration team] observed in various places great quantities of divers human bones, from which it may be safely concluded that the blacks along the coast of Nova Guinea are man-eaters who do not spare each other when driven by hunger.” (Mededeelingen van het Oost-Indisch Archief No. 1. Twee togten naar de Golf van Carpentaria, benevens iets over den togt van G. Pool en Pieter Pietersz, “Communications from the East Indian Archive No. 1. Two voyages to the Gulf of Carpentaria, along with something about the voyage of G. Pool and Pieter Pietersz,” J. Carstensz, 1623, J. E. Gonzal, 1756, Ludovicus Carolus Desiderius van Dijk, The Hague, first published 1859.)

Cannibalism in Africa

The Portuguese Dominican friar and missionary João dos Santos (c. 1560–1622), who spent over a decade in East Africa documenting the peoples and customs of the region for the Portuguese crown and church, included the following observations, dating from 1586 to 1597:

“The Muzimba kaffirs are so barbarous that they eat human flesh, and when they go to war they cut off the heads of their enemies and drink their blood from the skulls; and the flesh they roast and eat with great delight, esteeming it better than any other meat.” (Ethiopia Orienta, João dos Santos, Évora: Manuel de Lyra, 1609. Translation from “Eastern Ethiopia,” in Records of South-Eastern Africa, edited by George McCall Theal, Vol. 7, p. 192, Cape Town: Government of the Cape Colony, 1898.)

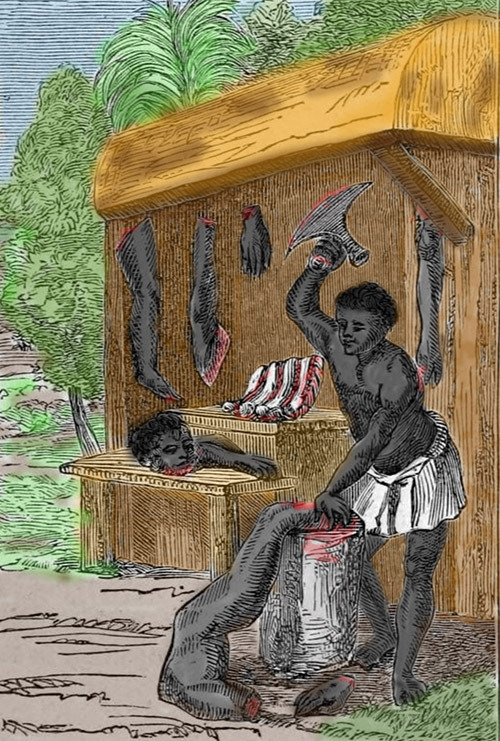

“CANNIBAL BUTCHER” WOODCUT FROM 1591

Above: This woodcut illustration is taken from Relatione del reame del Congo (“A Report of the Kingdom of Congo”), published in 1591 by the Italian mathematician and explorer Filippo Pigafetta (1533–1604). The book represents the earliest written report of African cannibalism circulated in Europe. Pigafetta produced the work at the request of Pope Sixtus V, who ordered him to record the account of Duarte Lopez, a Portuguese trader who had spent twelve years in the Congo during the sixteenth century. The image was created based on Lopez’s descriptions, not from direct observation. As a result, there are several notable inaccuracies. The structure shown resembles a European-style butcher’s shop rather than an African setting; the blade in use is a European butcher’s cleaver rather than the simpler cutting tools employed locally; and the physical features of the figures are clearly modeled on Europeans rather than Africans. Nonetheless, the value of Pigafetta’s work is uncontested, and provides a powerful insight into how Europeans experienced Africa at that time.

The Portuguese merchant Duarte Lopes (c. 1550–c. 1610), who resided in the Kongo (present-day Congo) from 1578 to 1591, later shared his experiences with Italian scholar and writer Filippo Pigafetta (1533–1604). In his accounts, he noted the following about the tribes of that region:

“In some parts of this kingdom, they eat human flesh, especially of their enemies taken in war, considering it a great delicacy, and they roast it over fires or boil it in pots, and this is done openly in their villages.” (A Report of the Kingdom of Congo, Filippo Pigafetta, Rome: Bartolomeo Grassi, 1591. Translation by Margarite Hutchinson, London: John Murray, 1881.)

The English sailor Andrew Battell (c. 1565–c. 1630), who was captured by the Portuguese and spent years in Angola and the Kingdom of Loango (present-day western Congo), recorded the following after his return to England around 1610, describing the Imbangala (or Jaga), a marauding group known for their cannibalism:

“The Imbangala are the greatest cannibals and man-eaters that be in all these countries . . . They eat man’s flesh, and when they take any captives, they keep them and fatten them, as we do cattle, and then eat them; and they eat the dead bodies of their enemies that they kill in the wars.” (The Strange Adventures of Andrew Battell of Leigh, in Angola and the Adjoining Regions, Andrew Battell, London: Hakluyt Society, 1901. Original narrative recorded c. 1610 by Samuel Purchas, published posthumously in Purchas His Pilgrimes, 1625.)

The Italian Capuchin missionary Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi da Montecuccoli (1621–1678), who spent over a decade (1654–1667) in Central Africa documenting the cultures and conflicts of Kongo and Ndongo, noted:

“The Jagas are a most barbarous people, who eat human flesh with great gusto; they kill their prisoners and slaves, roasting their bodies over fires, and they consider this meat more delicious than any other, offering it in their feasts as a sign of triumph over their enemies.” (Istorica Descrizione de’ Tre Regni Congo, Matamba et Angola, Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi da Montecuccoli, Bologna: Giacomo Monti, 1687. Translation from Historical Description of the Three Kingdoms, edited by John Thornton, c. 1687.)

The famous Welsh-American explorer and journalist Henry Morton Stanley (1841–1904), best known for finding the lost explorer David Livingstone and mapping the Congo, traversed Central Africa to trace the Congo River. His expeditions, including the 1874–1877 journey, produced vivid accounts of the Congo Basin’s peoples:

“The Wabembe are notorious cannibals; they filed their teeth to points, and openly admitted to me that they ate the bodies of their slain enemies, preferring human flesh to that of goats or cattle, which they roasted and consumed with relish.” (Through the Dark Continent, Henry Morton Stanley, London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1878.)

The English sculptor and explorer Herbert Ward (1863–1919), who served in the Belgian Congo Free State’s army, which waged war against the Arab slave traders in Central Africa, noted numerous instances of cannibalism among the Africans as late as the 1880s:

“The Bangala are notorious cannibals; I saw them prepare human flesh, cutting it into portions and roasting it over a fire, and they offered me a piece, which I declined, though they ate it with evident satisfaction.” (Five Years with the Congo Cannibals, Herbert Ward, London: Chatto & Windus, 1891.)

The German botanist and explorer Georg Schweinfurth (1836–1925), who mapped Central Africa and was renowned for discovering the Uele River and documenting its peoples, traveled through Central Africa (modern South Sudan and Congo) from 1868 to 1871, and noted that:

“The Niam-Niam are notorious cannibals; I observed them eating the flesh of their slain foes, and they told me it was sweeter than any other meat, a practice they carried out with no shame.” (The Heart of Africa, Georg Schweinfurth, London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1907.)

The Hungarian-British anthropologist and explorer Emil Torday (1875–1931), the early 20th-century leading ethnographer of the Congo Basin for the British Museum, lived among the Kuba, Bushongo, and other groups from 1907 to 1909. In his reports, he stated of the Congo tribes:

“They are not ashamed of cannibalism, and openly admit that they practise it because of their liking for human flesh; I saw them prepare the bodies of their enemies, roasting them over fires, and they offered me some, which I refused.” (Camp and Tramp in African Wilds, Emil Torday, London: Seeley, Service & Co., 1913.)

The British adventurer and colonial administrator Guy Burrows (1868–1919), who worked in the Belgian Congo Free State, noted during his time in that region (1895–1898) that:

“The native soldiers of the Force Publique [the Black soldiers fighting against the Arab slave traders] often engaged in cannibal feasts after raids; I once rescued a boy from being eaten, but my colleagues saw no need to interfere, as it was their custom.” (The Land of the Pigmies, Guy Burrows, London: C. Arthur Pearson, 1903.)

African cannibalism has continued well into the modern era. The British anthropologist Robert B. Edgerton (1931–2016), who conducted fieldwork in East Africa (Tanzania, Kenya) in the early 1960s, reported as follows:

“In the early 1960s, I was offered smoked human fingers and a slab of a young woman’s buttocks by a vendor in Tanganyika, who called it a ‘choice cut,’ though I declined to partake.” (The Individual in Cultural Adaptation, Robert B. Edgerton, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1965.)